Farmer in the Sky by Robert A. Heinlein

Farmer in the Sky by Robert A. Heinlein

Baen, $7.99, 290pp, pb, 9781439132777. Science fiction.

I first read Farmer in the Sky in college. It was one of these nifty little Heinlein novels I found in a great used book store up the street from my dorm, small books I hadn’t heard of. It was only after I’d bought the set (at fifty cents each) and read them that I later learned these were Heinlein’s juvenile novels. Farmer is one of those I’d remembered with some nostalgia, one of his Boy Scouts books. So I was happy to see this one turn up in the mail.

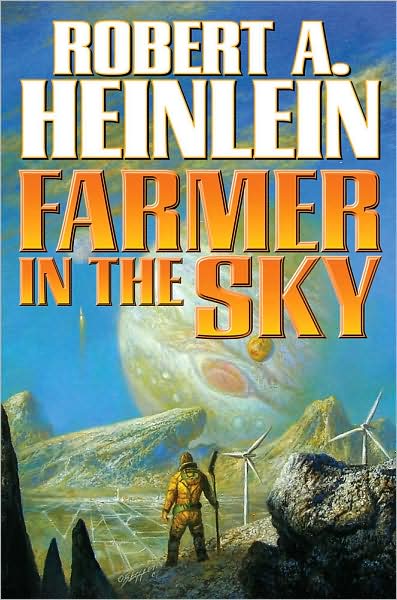

Fortunately for today’s readers, Baen is republishing the juveniles (and with gorgeous Bob Eggleton covers to boot). Unfortunately for Heinlein, some of his books don’t translate too well into today.

Farmer is the story of Bill Lermer, a teenaged Boy Scout living in an overcrowded southern California in an era of overpopulation (several of the juveniles have Earth as an unpleasant place to live because there are just too darn many people—1960s’ sensibilities). Bill and his dad (both geniuses, though you wouldn’t know it to look at them) are getting along in their efficiency apartment, living on the limited rations too large a population has imposed on society, and thinking about going someplace with a little more elbow room. Interplanetary colonization is a possibility, and our heroes (and the other half of their newly expanded family) are on their way to the Jovian moon Ganymede.

And we stumble across one of the first anachronisms introduced by the fact that the book was written in 1950: Bill checks out Ganymede in a book entitled A Tour of Earth’s Colonies. Ganymede was “first contacted in 1985, and the atmosphere project started in 1998,” which, while we don’t get an exact date, is about fifty years in the past at the time of the book. Yep, we sure knew where we were going at the end of the 20th Century. Unfortunately, reality and political will didn’t quite live up to those goals. There are several technological “not quites” in the book, but if you can get around them, it’s still a stirring story.

Bill and Dad wind up on Ganymede, in a situation where there are far more new colonists than there is equipment to get them up and running as farmers, difficulties ensue, but Bill (a typical Heinleinian hero—he thinks he’s average, and we only slowly learn that he’s exceptional) is able to succeed. Indeed, even with the hard work (which Heinlein doesn’t idealize), it seems an idyllic living (especially in this era of economic difficulty, there’s something very appealing about chucking it all and moving to a technological farming colony). Well, Bill gets himself set up, has run-ins with bullies and fools, forms friendships with other Heinleinian men, and overcomes natural and artificial difficulties, only to suffer a massive earthquake, which shuts down a lot of the necessary technology (there’s a heat shield to go with the atmosphere project, which goes off line). Again, Bill is able to survive, but reset back almost to the beginning.

There’s also the theme of Boy Scouting throughout the book: Heinlein was writing for a Scouting audience, and brings along the theme of scouting and the scouting ideals to explain why Bill is the superior man. Bill’s a troop leader in California, a founder of the ad-hoc Scout troop en route to Jupiter, and an intermittent member of the troop on Ganymede. Indeed, that on-board Scouting troop shows hints of another of Heinlein’s favorite themes: one of the kid-members is smart enough to realize that involving the adults with their version of Scouting is the last thing they want to do. Unfortunately, he can only hold out for so long. But the political independence and idealism he shows will be echoed in other novels.

I think the only place Heinlein fell down on the job, in this case, was at the end of the book (and indeed, he probably could have chopped out the offending two chapters without any difficulty). After the disaster, when Bill’s farm is unworkable and waiting for some help, Bill joins an exploration party to open up more land elsewhere on Ganymede. While on the trip, they discover alien technology, left in a cave lo these many centuries. I’ve read the book several times, and I still don’t know why he bothered to stick that in; it doesn’t flow with the rest of the story, and isn’t at all necessary. Actually, if you just skip chapters 18 and 19 (“Pioneer Party” and “The Other People”), you’ll probably enjoy the book more. At any rate, it’s a good story.

As with the other Baen republications, this one comes with a brief introduction (by William H. Patterson, setting up Heinlein’s state of mind when he wrote the book) and a longer afterward (on terraforming) by Dr. Jim Woosley. This afterward is actually pretty good, a nice technological look at how it would be possible. But as with all the books, they’re not necessary. You’re going to get this one for your up-and-coming sf readers, because it tells a great story, and also shows the psychology of the science fiction reader in 1950.